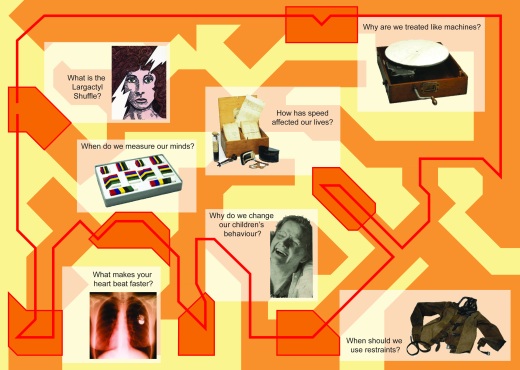

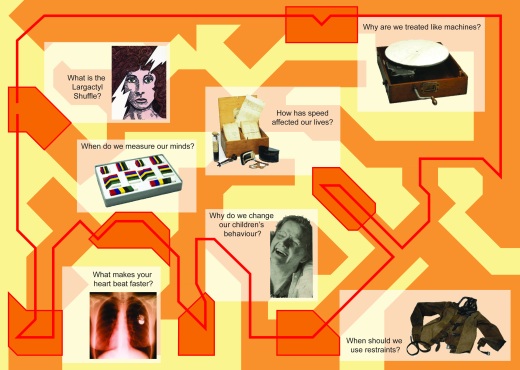

Two stops on our walk about the history of mental health at the Wellcome Collection in the Science Museum for Cooltan Arts Largactyl Shuffle@Science Museum LATES

City life

Innovations such as the steam engine and the telegraph revolutionised the speed of transport and communications, spurring on the expansion of the British Empire, and this fuelled the growth of cities. The rise of industrialised factories in combination with the loss of the last common lands, drove masses of the poor from the countryside into the city, leading to an explosion of the urban population. Overcrowding and insufficient sanitation led to horrific epidemics, and people lived in mortal fear of previously unheard of diseases such as Cholera. In the early 19th century humoral medicine was still practiced. A healthy body, free of disease and with an untroubled mind was the result of a well-balanced constitution. An imbalance in one of the four bodily fluids, or “humors”, caused disease or worry – for example an excess of phlegm was associated with lethargy, black bile was the root of melancholia, those with aspic tongues had a surplus of choler, and a rush of blood to the head would lead to mania.

Traditional practices such as cupping, bleeding and purges could be used to reduce an excess of a specific humor thereby redressing the balance. As medical science advanced though, a new conception of disease came about. The connection between, over populated cities and the spread of disease by microorganisms, ushered in an era of innovative public works which addressed the provision of clean water and the efficient removal of sewage.

The Answer Aint Restraint

There was also a belief that personal relationships were being undermined too by the new city living. Faster transport facilitated the mass movement of workers, eroding communities and minimising personal relationships. Private ownership trumped social welfare and many were left susceptible to the depressions of lonely lives, lived in alien environments. New psychiatric institutions appeared, and then, as now, access to open spaces and nature was seen as key to relieving emotional stress. The Bethlem hospital itself, changed sites multiple times in order to escape the continually spreading city; seeking out open spaces, where those in distress could find calm and recover from the trials of the modern life.

When a manic or “raving” person was perceived as threatening, mechanical restraints such as these manacles and straight waistcoat were commonly used to control erratic behaviour. However, when the scandalous treatment of patients in these institutions was exposed there was a public outcry, and people demanded an end to the inhumane treatment. The physician John Conolly, who was a leading light in the non-restraint movement, called for a revolution in care. He said that – “mere abolition of fetters and restraints constituted only a part… Accepted in its full and true sense, it is a complete system of management”. The holistic practice he championed focused on treating patients well, providing them with good nutrition, clean clothes, and a stimulating, calm environment. Fellow physicians were appalled, one calling the system “a gross and palpable absurdity, the wild scheme of a philanthropic visionary, unscientific and impossible”. Thankfully, however, Conolly’s principles were successfully incorporated into medical practice, and patients in mental distress were increasingly treated with care and respect.

Nearly 160 years on these issues are still being debated. The need for and potential abuse of dangerous physical restraint techniques is questioned, and there is concern that chronic underfunding is resulting in unacceptable conditions and inhumane treatment in our care homes. An ever expanding pharmacopeia may have supplanted mechanical restraint in many situations, and many in society choose to turn a blind eye to those in dire need, but the problems remain. Again we must ask ourselves – are these interventions are humane? and when do they mask poor institutional practice?